I've written before about what I believe might be the first, tentative steps into realizing what I consider to be one of the defining truths of my life: that there is no God or gods.

But that's only part of the story. There's also that moment when I realized I wasn't alone. That there was a name for people such as myself. And that there were a lot of us out there. And that word was "skeptic."

I have always read voraciously. It started at an early age. We'd get The Weekly Reader at my school, and a couple of times each year, they'd have a page where you could go through a bunch of books they offered and check them off. The teacher would collect everyone's order sheet — and a check from their parents — and send them off. A few weeks later, we'd all get our books.

The other kids in my class would get one or two. I'd get eight to ten. And I'd read them almost as soon as I got them home.

At around age nine, I became fascinated by the occult. Ghosts, aliens, poltergeists, bigfoot, the Loch Ness Monster, the Bermuda Triangle, Atlantis, the Nazca lines . . . you name it, I probably believed it and read at least one book about it. (Well, except vampires and werewolves. Those were never on my radar.)

I scared the crap out of myself. Convinced myself that my house was haunted. That aliens were abducting people left and right and I might be next. That Bigfoot might be wandering around in the forest right behind my house. That every sound in my house at night was something unspeakable coming specifically to get me.

I didn't sleep a lot. :)

I eventually expanded my literary palate to include science fiction, fantasy, and horror. I read my first Steven King novel (The Shining) at age twelve. My pendulum swung all the way over in the other direction from belief and I started to realize that the things that seemed so plausible at nine or ten were silly and rather childish from the vantage point of the advanced age of twelve. I mean, come on. Erich von Daniken's ancient aliens were about as likely as . . . as a plesiosaur alive after 65 million years in a murky lake in Scotland.

I got completely away from non-fiction1 and consumed only fiction for many years. I must have been in my late twenties or early thirties when I picked up two books written by Carl Sagan. I had done another one of those turn-arounds and was now heavily into non-fiction2: science, psychology, self-help (I know, I know . . . skepticism is a process), that kind of thing.

Then, I read a book called The Demon-Haunted World, and the world made so much more sense. I had a category to put myself in. Not only could I confidently say, "I'm an atheist," I could also now confidently state, "I am a skeptic."

And then I read Pale Blue Dot.

There's one passage from the book that never fails to bring a tear to my eye. It is so beautifully, passionately written. It transcends science and literature and speaks directly to the heart, as it were.

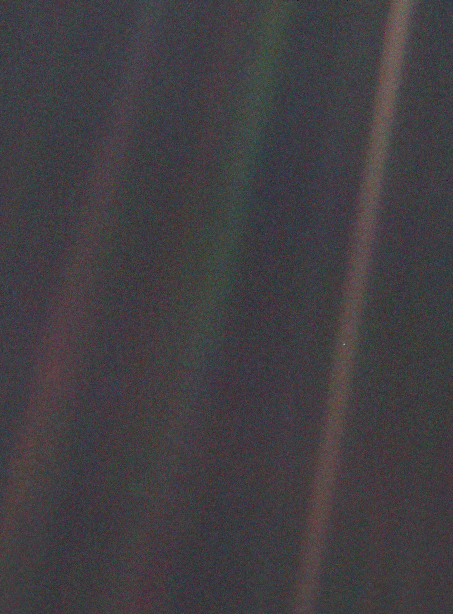

But first, some background. The year was 1990. The Voyager 1 spacecraft had completed its primary mission after twelve years and was about to depart the solar system forever. Dr. Carl Sagan, realizing that it was likely we would never again get the chance to get a "family portrait" of the Solar system from that vantage point, managed to convince NASA that they needed to turn the craft around and have it take a picture of all visible planets (Earth, Venus, Neptune, Uranus, Jupiter, and Saturn) from the perspective of six billion kilometers away from Earth.

That's 6,000,000,000 kilometers — approximately 3.7 billion miles. So far away, messages from Voyager 1 to Earth took nearly 5.5 hours to reach us at the speed of light.

NASA agreed. They captured images of the outer planets first, fearing that by aiming their cameras too close to the sun to include Earth and Venus, they would damage the camera. And then, finally, they aimed their camera at Earth.

The resulting image is the one we now call The Pale Blue Dot. You can see it up at the top of this post. Click it and you'll go to a larger version of it.

That brown streak is an artifact of how close to the sun the cameras were aimed in order to capture Earth. It isn't a real structure.

What is real is that tiny blue pixel in the streak. That tiny blue point of light — smaller than a full pixel — is Earth.

Here are Dr. Sagan's words. The ones that bring a tear to my eye.

From this distant vantage point, the Earth might not seem of any particular interest. But for us, it's different. Consider again that dot. That's here. That's home. That's us. On it everyone you love, everyone you know, everyone you ever heard of, every human being who ever was, lived out their lives. The aggregate of our joy and suffering, thousands of confident religions, ideologies, and economic doctrines, every hunter and forager, every hero and coward, every creator and destroyer of civilization, every king and peasant, every young couple in love, every mother and father, hopeful child, inventor and explorer, every teacher of morals, every corrupt politician, every "superstar," every "supreme leader," every saint and sinner in the history of our species lived there – on a mote of dust suspended in a sunbeam.

The Earth is a very small stage in a vast cosmic arena. Think of the rivers of blood spilled by all those generals and emperors so that in glory and triumph they could become the momentary masters of a fraction of a dot. Think of the endless cruelties visited by the inhabitants of one corner of this pixel on the scarcely distinguishable inhabitants of some other corner. How frequent their misunderstandings, how eager they are to kill one another, how fervent their hatreds. Our posturings, our imagined self-importance, the delusion that we have some privileged position in the universe, are challenged by this point of pale light. Our planet is a lonely speck in the great enveloping cosmic dark. In our obscurity – in all this vastness – there is no hint that help will come from elsewhere to save us from ourselves.

The Earth is the only world known, so far, to harbor life. There is nowhere else, at least in the near future, to which our species could migrate. Visit, yes. Settle, not yet. Like it or not, for the moment, the Earth is where we make our stand. It has been said that astronomy is a humbling and character-building experience. There is perhaps no better demonstration of the folly of human conceits than this distant image of our tiny world. To me, it underscores our responsibility to deal more kindly with one another and to preserve and cherish the pale blue dot, the only home we've ever known.

To me, those three paragraphs pretty much sum up my view of our place in the universe. Why it's so important to further our knowledge and turn away from unprovable beliefs and ideologies that do nothing but stifle progress in the name of petty arguments over what amounts to nothing. Belief isn't going to save mankind from whatever our species' eventual fate might be, whether it's extinction by our own hands or something we have no control over, like a new disease, environmental disaster, or a big rock hitting our planet.

Science might. There are no guarantees. But there is no evidence that anyone is watching over us, ready to save us if we just know the right words to use when asking. Or ready to punish the entirety of our species for the infractions of a small percentage because of some foolish, petty whimsy. "You don't deserve to live, because you ate meat on a Friday. Pushed a button. Wore two kinds of fabric. Ate meat from the wrong animal. Loved the wrong person. Didn't bow to the east to recite your prayers. Listened to the wrong leader. Drank the wrong drink. Thought the wrong thoughts. Believed the wrong things."

If we're going to survive, it will be because men and women of science, not faith3, figured it out. And that is what I have faith4 in.

Today's post is inspired by GBE2 (Group Blogging Experience)'s Week 115 prompt: Faith.

- I realize now that categorizing these books as 'non-fiction' is laughable, but at the time, that is how they were marketed. Which is one reason I probably had such a protracted period of time when I believed whole-heartedly in such nonsense: after all, "They" wouldn't allow a book to claim it was non-fiction if it wasn't, would They?

- Actual non-fiction! Like Carl Sagan's books and stuff by people with real edumacashuns and degrees from universities that aren't made up. People who have Science and Data to back up their claims instead of a lot of supposition and things they have extracted from their own asses.

- As in belief with no evidence — or even in defiance of evidence to the contrary — which is what is usually meant when used in this sense.

- Evidence-based trust, as in, "I have faith the sun will rise tomorrow," because we have scientific evidence, not because someone sang it into the sky or sacrificed a virgin to it or prayed it out of the darkness.

2 comments:

This is a great piece of writing. Love the Carl Sagan excerpt.

Thank you. What prompted this whole post was a video someone made on YouTube of the image with a voiceover of Sagan reading that excerpt.

It just destroys me every time.

Post a Comment